|

THE SHOW

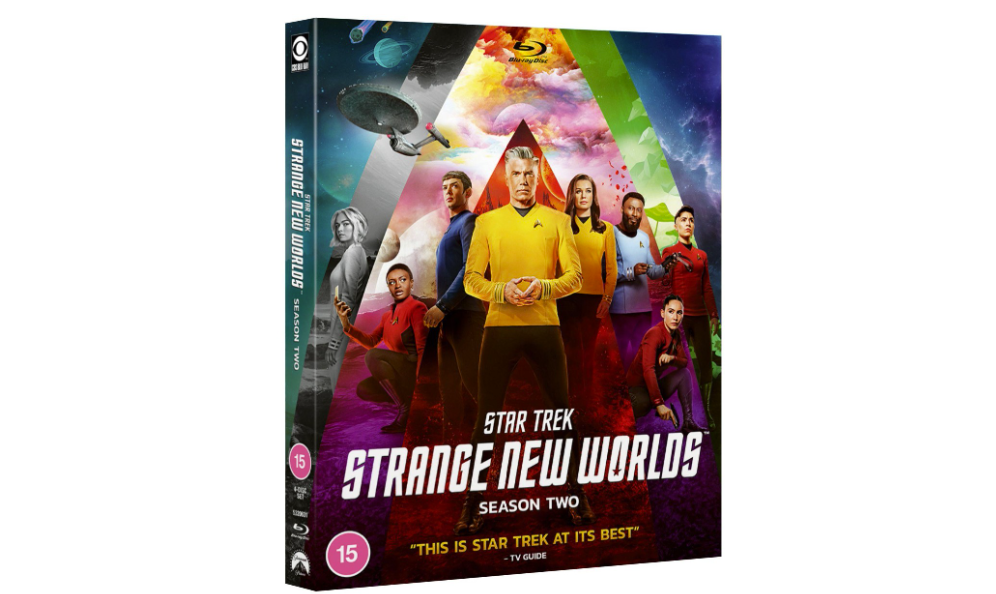

Star Trek Strange New Worlds season two marks a shift in the show's format, with its sophomore year taking bold steps in changing character relationships and embracing a larger ensemble cast. The decision to give each bridge member their own story arc provides depth to characters like Dr M’Benga, Ortegas, and La'an Noonien-Singh. However, the drawback is Captain Pike, played by Anson Mount, takes somewhat of a backseat, lacking a distinct character arc compared to season one with a larger focus on his romantic relationships this time. The show like Pike takes risks, such as the crossover episode with the animated Trek comedy Lower Decks, "Those Old Scientists," a standout moment in this new Golden Era of Trek that successfully blends zaniness with live-action without compromising either show's integrity. The subsequent three-episode run, featuring a dark war episode and a musical episode titled "Subspace Rhapsody," is a high for its creativity and versatility for the franchise. The weakest parts of the season are the first couple of episodes, particularly the premiere, "The Broken Circle," and the finale, "Hegemony”. Ultimately, the success of "Strange New Worlds" can be attributed to its well-developed characters, with particular attention given to the evolving relationships between Chapel and Spock, La'an and Kirk, and the bond between M’Benga and Chapel, forged during the dark days of the Klingon War. SPECIAL FEATURES Disc One features a range of deleted scenes - a prized commodity on Star Trek releases. "The Broken Circle." shows a scene, set on Starbase One, providing the type of valuable insights into Federation tensions and priorities that fans love when people are around a table talking shop. Disc Two features more deleted scenes and extended scenes. A notable scene from Episode 5, "Charades," features a humorous exchange between 'human' Spock and Una in a bar, adding further comedic touches to a really enjoyable episode. Episode 6, "Lost in Translation," presents a cut corridor conversation between Una and Pike, offering some additional character-building moments. “Lost in Translation," also includes an extended version of Una and Pelia's shuttle scene. "Those Old Scientists," fans will be disappointed with only just one extended scene. Disc Three finally houses the majority of special features including some more deleted scenes, segments on props, and costumes, and the development of the revised Gorn appearance. This insightful deleted scene is an alternate version of the iconic Klingon sequence from "Subspace Rhapsody," which highlights it was the right decision to feature a Klingon K-Pop version in the final episode. The first feature of Disc Three focuses on props, such as the Vulcan lute and the 3D printing process for the teapot used in "Charades." The second feature explores costumes, providing cosplay references and chronological insights into their appearance. The Gorn feature details the development of Gorn appearance and costumes, while the "Singing in Space" feature, is dedicated to the musical episode "Subspace Rhapsody’. The final feature, "Exploring New Worlds," covers the making of the season and taking the time to focus on the ten episodes that make this such a memorable year. It's a real shame that there's a lack of a feature dedicated to the iconic crossover episode. Now with the Hollywood strikes over and Star Trek: Strange New Worlds about to begin shooting again in Canada this Blu-ray will give fans something to enjoy as we continue to the long but highly anticipated season 3 in possibly 2025! 4/5 Star Trek: Strange New Worlds Season 2 Arrives on DVD, Blu-ray™, and 4K UHD™ on December 4 Star Trek: Picard's third and final season arrives on blu-ray and delivers a thrilling and emotionally satisfying conclusion to the epic journey of Jean-Luc Picard and his crew... for now! The season explores the consequences of the Dominion War and brings back The Next Generation together again to save their own and the Federation. The camaraderie and genuine connection among the cast members elevate the storytelling, creating a powerful and memorable viewing experience for Trekkie and newcomer alike.

The blu-ray is fitting for a journey that has spawned over thirty five years packed with special features and insight offering a mix of behind-the-scenes content, deleted scenes, audio commentaries, and even a hidden Easter egg. In an era where behind-the-scenes materials are readily available online if at all, the five vignettes included in the set provide insights into the production of Season 3. However, it's noted that some previously released behind-the-scenes segments from The Ready Room are missing once again on a Star Trek home video release. The highlight of the behind-the-scenes features is "The Making of the Last Generation," a 42-minute documentary covering the entire final season. It includes interviews with writer-producers Jane Maggs and Brian Tatosky, providing a comprehensive look at the production, writing, and performances that shaped the iconic season. Another standout is "Villainous Vadic," a detailed interview with Amanda Plummer and various producers, shedding light on bringing the character of Vadic to life and her personal connection to the franchise through her father Christopher Plummer who made an unforgettable appearance in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country. "Rebuilding the Enterprise-D" explores the design of the iconic starship, featuring insights from production designer Dave Blass and art director Liz Kloczkowski who recently appeared on our podcast, The A24 Project.. The Blu-ray also includes a 42-minute Q & A panel with key cast and crew members, providing additional context and discussions held before the April finale IMAX screenings. The set includes relevant deleted scenes, such as those from episodes like "The Bounty," "Dominion," "Surrender," "Võx," and "The Last Generation." These scenes offer additional depth to the narrative, providing insights into characters like Data, Lore, Worf, and others. The deleted scenes are considered notable, with some viewers wondering why certain scenes weren't included in the final episode edits. The Blu-ray's strength lies in its five full-length audio commentaries, a rare treat for fans. Showrunner Terry Matalas participates in all commentaries, and notable contributors include Jonathan Frakes, Jeri Ryan, Todd Stashwick, Gates McFadden, Michelle Hurd, LeVar Burton, and Brent Spiner. The commentaries cover episodes like "The Next Generation," "Seventeen Seconds," "The Bounty," and "The Last Generation," providing both spirited and introspective discussions on the series' highlights. Lastly, the release includes a hidden Easter egg, "One More Hand," a 6-minute extended recording of the Ten Forward poker game that closed out "The Last Generation." The Blu-ray edition not only delivers a fantastic set of episodes that marks a generations final journey but come packed with extras that offer an exclusive peek behind the scenes, providing a deeper appreciation for the creative process and the evolution of the beloved characters. Now bring on Star Trek: Legacy! 5/5 Star Trek: Picard - The Final Season Arrives on DVD, Blu-Ray and Blu-Ray Steelbook on November 20th. - Lee Hutchison The Insider

Zoo Southside - August 24-27 Look into the human face of greed – live acting, visuals and a binaural soundscape that gives you the chills. The Cum-ex tax scam: 50 billion GBP "robbed" from the treasuries around Europe! The use of headphones and 3D-sound creates an intimate connection with the cynical financier on stage when he is interrogated at a party in the club, in the shower, in a bank in Zürich. Did you know you were robbed out of tens of billions in something called the Cum-ex tax scam? I doubt it. The Cum-ex tax scam was a complex financial fraud scheme that exploited a tax loophole in several European countries, between the early 2000s and 2012. The scheme, which involved extensive coordination and manipulation of financial transactions, resulted in the misappropriation of billions of euros in wrongfully claimed tax refunds. Our insight into this world of corruption and the rats sneaking between the cracks amongst some of the biggest names in finance is played by Christoffer Hvidberg Rønjethe, a nameless insider, as the type of trim and well-dressed corporate man who is instantly recognisable to us all who uncovers the CumEx tax evasion strategy then finds himself seduced into being a key and willing participant. He is compelling to watch inside his literal and metaphorical box as we watch his fall from bean counter to allowing power and money to have him powdering his nose and then losing control towards his family and his grip on reality as he tries to balance the high wire act of massive corporate greed and attempting to justify it to himself and prosecutors. The audience wears headphones which allow us to hear other characters interacting with our insider, the pounding of the dancefloors where these criminals hide in plain sight, the scribble of a pen, and the sound of every bit of stress from elevated breathing, to manic movement straight into ears and allows every audience member to engage equally no matter where their seat is within the venue. The use of the large box on stage where the drama unfolds throughout was a very surprising choice for me as it immediately drew parallels with one of the most popular plays about financial greed, The Lehman Brothers. While slightly smaller the box in The Insider uses many of the same techniques from writing on the plastic, backscreen projection and one of the same minimal pieces of furniture in terms of a filing cabinet. The play is only an hour and can only uncover so much in that time and it takes the right approach to make the best use of the ticking clock by focusing on how and why someone could be such a willing participant in a scheme. Our insider comes from a part of Germany where he has no right to be as successful as he has and the opportunity to go from cultural outsider to exposed to the best in life and all the trappings is something that will get the audience wondering if that could be them and would they too would do the right thing when the moment comes. - Lee Hutchison 4/5 Book your tickets here > https://tickets.edfringe.com/whats-on/insider A Highly Suspect Murder Mystery - Murder on the Disorient Express

Aug 21-26 - theSpace @ Surgeons Hall - Theatre 1 A legendary detective killed aboard a famous train – but who had locomotive for murder? Award-winning mystery maestros Highly Suspect return with a new hilarious interactive murder mystery which the audience must solve! Featuring a fiendish plot, evidence to examine and cryptic clues to crack, can you deduce whodunnit? Fun, frivolity and fatalities guaranteed! ‘Providing plenty of laughs and a few twists… I challenge you not to feel exhilarated by Highly Suspect’s hugely successful production’ ***** (EdFringeReview.com). Mervyn Stutter’s Pick of the Fringe 2022. Sold out, 2021-2022. I have some experience with murder mysteries shows - my wife runs a theatre company that produces murder mysteries, and we met when she hired me for a show (a story for another occasion!). So it is always interesting to visit another murder mystery company to see how they run their shows - and Highly Suspect does a great job. Set on a parody version of the infamous Orient Express, there is a cast of characters there to celebrate the retirement of a familiar detective. As the murder is discovered, the audience is given a folder of various clues to figure out the killer. At first glance, it can seem like your group is given a lot of work to do - but the puzzles are challenging, though not overly difficult. The cast knows how to handle audiences of all skill levels, with their characters mixing among teams, creating a friendly atmosphere, and happily giving out hints to make the experience fun, not frustrating. Whether you are successful or not in guessing the killer, this cast is there to have fun with the story and the audience. Definitely suggest going with a group of 3 or more. - Phillip Gilfus 4/5 Book tickets here > https://tickets.edfringe.com/whats-on/highly-suspect-murder-mystery-murder-on-the-disorient-express SCOTS

Aug 22-27 - Ghillie Dhu - Auditorium The musical history lesson that no one asked for but everyone needs! A Play, A Pie and A Pint shares the true(ish) story of our nation: its past, present and future, its triumphs and failures, all told by a figure who has seen it all... Scotland’s greatest invention and storyteller, The Toilet! From award-winning duo Noisemaker, Scots is an irreverent and rousing musical journey through the history of Scotland, that replays some of our nation’s most iconic (and forgotten) stories to answer the fundamental question: What makes a country? Ticket includes a pie and a pint. Part of MadeInScotlandShowcase.com. There are several Fringe shows that sound strange to describe - "You should go see this show about a toilet that sings about the history of Scotland. I mean, there are scenes that'll make you cry in your beer, and others that will make you cheer with joy. Also you get lunch." Yet this is SCOTS from Glasgow-based A Play, A Pie and A Pint that takes the audience on a trip through Scotland's people, from Kenneth MacAlpin to MSP Monica Lennon. Any historical telling can simply go through a catalogue of kings and queens, but SCOTS dives deeper into the people who charted the course of Scotland. There is a question posed on a back wall during the show - "What Makes A Country?" Is it the inventions produced by the people that changed the world? Is it the amazing women who made their voices heard? Is it social progress? It's up to the audience to figure it out - and to see how all this centers on those who use the toilet. As with all shows from this theatre company, the audience does get a pie and pint to enjoy during the show. Whether you're Scottish or not, this production is dynamic from all the players - this is one of the top shows you'll be talking about during the Fringe. - Phillip Gilfus 5/5 Book tickets here > https://tickets.edfringe.com/whats-on/scotstickets.edfringe.com/whats-on/scots |